- May 2, 2013

- Applied Research

- Comments : 0

NBIF Researcher Explains His Link To Google Street View

By Shane Rockland Fowler for The Daily Gleaner | Link to original article (subscribers)

Last year Google announced that it had 20 million gigabytes worth of pictures taken for its popular Street View technology.

Those pictures, stitched together, allow anyone to jump online and virtually fly through five million miles of road covering 39 countries. It’d be a heck of a digital road-trip, one that would start in downtown Fredericton where some of the very first pictures for the service were taken — and not taken by Google, mind you, but by students and researchers at the University of New Brunswick.

Go back 13 years to 2000. The tech landscape was very different then. There was no Twitter, no iPhone, and no Facebook. But the concept and groundwork for Street View were already well underway here in Fredericton.

“The basic idea, we did it 10 years before,” said Dr. Yun Zhang. “We published at least seven years before Google even started.”

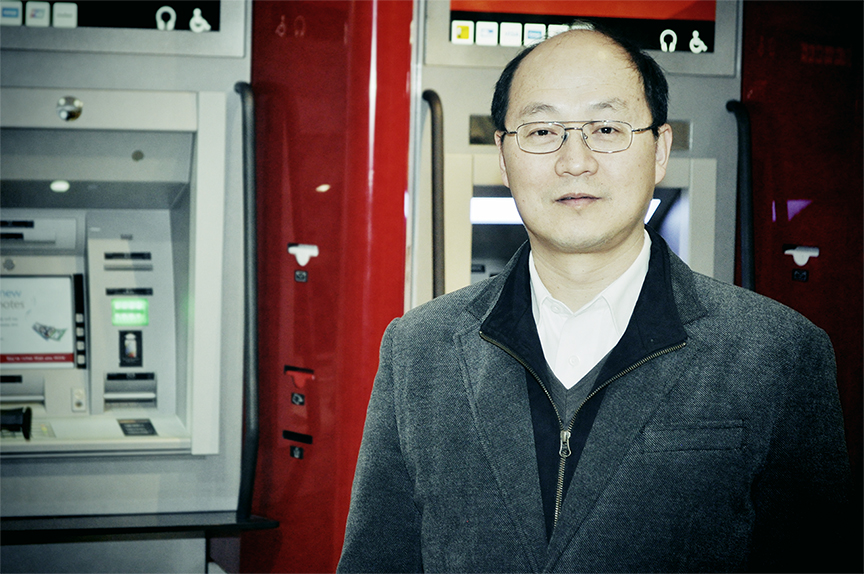

Zhang, originally from China, is a good-natured professor at UNB’s Department of Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering Department. After studying in Germany and Calgary, he came onto the street view project led by Y.C. Lee in 2001. That project had one or two cameras mounted on top of a tripod. Those cameras would be rotated, by hand, to take pictures of an area in 360 degrees. The pictures were then stitched together to provide a panoramic view of the area.

“We always used a tripod to mount the cameras,” said Zhang. “In one case we had two cameras (on a single tripod) and with that you could measure distance. You could measure the distance from the camera to any point in the picture. So you click anywhere and it measures 3-D distance.”

The project was designed to give a person an idea of where they were orientated without actually being there.

“At that point there was no online mapping,” explained Zhang. “We only had a local computer, so we put it on the local computer. If you went to OnlineGIS then you could orientate yourself there.”

While this concept seems old by our standards today, with Google’s Street View being available to everyone for the past five years, at that time it was an unknown and untested concept. The technology worked and the results were published, but seven years ago no one knew if there was a market for what the team unearthed.

“If we had applied for a patent, then Google would’ve had to use our patent. Unfortunately we didn’t,” laughs Zhang.

As a testament to how similar the results are, Zhang compares a photo of Fredericton’s downtown courthouse taken by his research team 10 years ago and one taken recently by Google’s Street View. They’re identical, despite being a decade apart, and one was taken by a company that’s worth almost $100 billion.

Patents take time and money. Often, if researchers cannot think of a way to monetize their work, they’ll simply publish their work, leaving it open for others to find ways to make them lucrative. Licensing their technology is another option, one that the department often does with other projects. Those have led to some high profile clients such as NASA and the Canadian Department of National Defence.

Zhang doesn’t have 100 per cent proof that Google went through his team’s publication for Street View, but he’s got some pretty convincing evidence.

“We published this paper in 2001. And in 2007 Google started Street View. The principle is exactly the same,” said Zhang. “Also in 2006 they asked me to join their team.

“I turned down Google because I just became a Canadian Research Chair, so I didn’t want to leave the university after getting such honour.

“Also before this, at an international conference, Google’s CEO was giving a keynote speech,” said Zhang. “After that speech I talked to him, told him I come from the University of New Brunswick and he immediately said ‘Ah, I know UNB.”

Zhang said he’s had other UNB colleagues treated the same by other Google employees working with mapping.

“From all this information, I can see their technology is somewhat inspired by our technology.

“What they did differently,” explained Zhang about Street View, “because ours was just proof of concept and we just used one camera that we’d rotate and take a few images and stitch them, they put a lot of cameras together.”

All this is ancient history as far as Zhang is concerned. He’s gone on to develop several other technologies in advanced geomatics image processing that are just as impressive — from sharpening image qualities from space to being able to judge how fast cars are moving simply based on satellite photos, Zhang has quite a few other impressive projects that are being developed.

“Some of those are being patented,” laughs Zhang. “Others we license and other we still just publish.”

Despite the technology that he helped to develop adding millions of dollars to Google’s coffers, Zhang isn’t bothered that he or the team he worked with didn’t get filthy rich from their work.

“Now it’s worldwide, everywhere,” said Zhang. “This created an industry, a lot of people working on it.”

“People go on and say ‘Look! There’s my house!’ That was us. We did that.”

Shane Rockland Fowler is a STU journalism graduate and current biology major at UNB. His goal is to take the hard, precise nature of science and make it accessible and topical to the public without upsetting either side too much.