- 17 mars, 2014

- R3

- Comments : 0

NBIF-funded biomedical researcher receives R3 Award

Leading The World From Fredericton

By Quentin Casey for the Telegraph Journal | link to original article.

As a graduate student at the University of New Brunswick, Kevin Englehart took a course that examined how our brains communicate with our muscles through a complex network of nerves and electrochemical signals.

“It was the most sophisticated communication system I had ever seen, and it was all completely natural,” he recalls. “The biological communication system in our bodies was 10 times as sophisticated as any artificial or man-made system I had ever seen. I became totally fascinated with that.”

While completing his PhD, Englehart became enthralled with the idea of creating devices to tap into that biological system. Fifteen years later, his research has significantly advanced the field of bio-prosthetics.

On Thursday, Englehart will be one of three New Brunswick researchers honoured at the fourth R3 Gala, hosted by the New Brunswick Innovation Foundation. Englehart (along with UNB’s Felipe Chibante and Rodney Ouellette, of the Atlantic Cancer Research Institute) will receive the R3 Innovation Award for Excellence in Applied Research.

“I certainly wasn’t expecting it,” Englehart says in an interview. “You keep your head down and do your work, and all of a sudden something like this comes along. It’s nice.”

Englehart is the director of UNB’s Institute of Biomedical Engineering, an organization with a rich history of innovation.

The Institute was launched in 1965 by Robert Scott, a UNB professor of electrical engineering from 1959 to 1995. Scott was the Institute’s director for 25 years, over which time it became internationally renowned.

Englehart says Scott invented a whole new area of research, one that is now allowing amputees to power prosthetic limbs with their natural muscle signals.

“When you contract your muscles, in addition to your muscles bulging, there’s electricity produced,” Englehart explains. “Bob Scott was the first one to figure out that you could actually harness that signal and decode it and use it to control a prothesis.”

In short, Scott’s pioneering research helped produce key electronic aids for the disabled.

“We’ve carried on his legacy,” Englehart says. “And we have continued to lead the world in this area of research.”

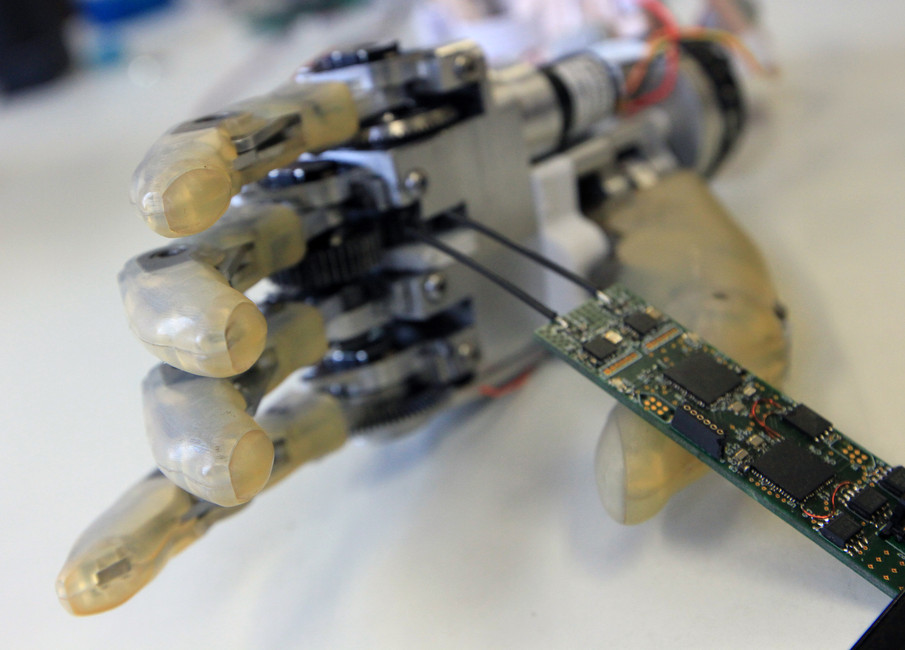

Englehart’s research, at its core, involves tiny computers that can be placed in prostheses. The devices are able to decode the body’s electromagnetic signals, translating them into movements and commands. In other words, the device tells the prothesis what the brain wants it to do. Thus the patient needs only to think about a task – such as lifting a cup of coffee – and the prothesis will make the appropriate movements to turn the thought into a reality.

“It learns what the person wants to do,” Englehart says.

The technology produced in Englehart’s lab has been tested in-house but has not yet been put through clinical trials. One challenge is the cost: up to $100,000 to fit just one amputee with a personalized prosthesis.

Another challenge is the rise of outside competitors, including some of Englehart’s former students, such as Blair Lock and Levi Hargrove. Both Lock and Hargrove worked at the Center for Bionic Medicine (Hargrove still does; Lock recently departed). The centre is part of the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago, a world-renowned hospital that recently developed the world’s first thought-controlled bionic leg. The pair have also started a company, Coapt, which is competing with Englehart’s technology.

Kevin Englehart director of institute of biomedical engineering at the University of New Brunswick is seen with the department’s prosthetic hand Wednesday afternoon.

“It’s good and it’s bad,” says Englehart, who is originally from Fredericton and completed his undergraduate, graduate and doctoral degrees in engineering at UNB.

“Obviously, it would be great for us to be the only ones in the field right now and have a clear path to commercialization. But my students are doing great things in terms of coming up with other ways of applying this.”

Englehart has also developed an electromechanical prosthetic hand, but, again, competition is an issue.

“We’re not really sure if we’re going to be able to commercialize that part of it,” he says. “It’s 90 per cent done, but in the four to five years we’ve been working on it, at least a half-dozen other research groups and companies have developed competitive products. At the moment, it’s a really great research prototype. We’d like to think someday we could commercialize it, but we’re not really sure right now.”

More immediately, Englehart is in talks with a Boston company about commercializing technology for aiding upper-limb amputees. It would be in competition with Coapt’s technology.

Still, Englehart is sanguine. His lab’s research has been disseminated to the world, and though that might diminish his commercial prospects, it’s a good thing for amputees.

“We’ve created a whole network of competitors with ourselves, but ultimately the big picture is for this technology to become available so that people who need artificial limbs can receive it and benefit from it,” he says.

Kumaran Thillainadarajah, the CEO of Fredericton-based Smart Skin Technologies, a nanotechnology company, has collaborated with Englehart on a couple of research projects, both having potential for commercialization.

“He takes on a lot of responsibility,” Thillainadarajah says. “He’s very on the ball. He’s accomplished a lot in a very short period of time with our tools. I’ve done a few different research projects and the quality of work being done by his team is far superior to anything else I’ve seen.”

Thillainadarajah has also used Englehart as a talent scout for Smart Skin. “Kevin has a knack for identifying top students at the university. For the past four or five hires we’ve relied on him to find us candidates.”

Englehart is hoping to push his technology beyond the realm of upper limb-amputation uses, perhaps into other health applications or even into unrelated fields such as gaming. Those commercial ventures may prove successful, or perhaps not. And he seems OK with that fact.

The “most satisfying” moments arrive when amputees are first outfitted with his technology, Englehart finds.

“We all want our own personal achievements, but in the end we want to see the technology get out there so people can benefit from it.”